LI. ipseity

on whiteness when you are black

My friend Seth asked me if I’ve ever wanted to be a man. Of course a call with him would begin this way. Seth is in the car in D.C., Baltimore, Annapolis; I am walking in the West Village, BedStuy, Midtown. Our calls follow the cadence of commute: eight thirty in the morning, seven thirty in the evening, rare lunchbreaks. During this call I was passing a playground, sprung up randomly (as city playgrounds do) on a street of restaurants with well-peopled terraces: When do these people work? Seth asked me if I’ve ever wanted to be a man and I responded quickly that I have not. He was surprised. He said you’ve never looked at all the men in power and said, “if only I could trade places.” His question was not of gender but of power, and implicitly state power, impersonal power, the Rule of Law. That has never really appealed but, I told Seth, what I have felt for the majority of my life (thankfully a receding majority with each passing year) is an envy of whiteness. To be a White American Woman. Then I could really get something going.

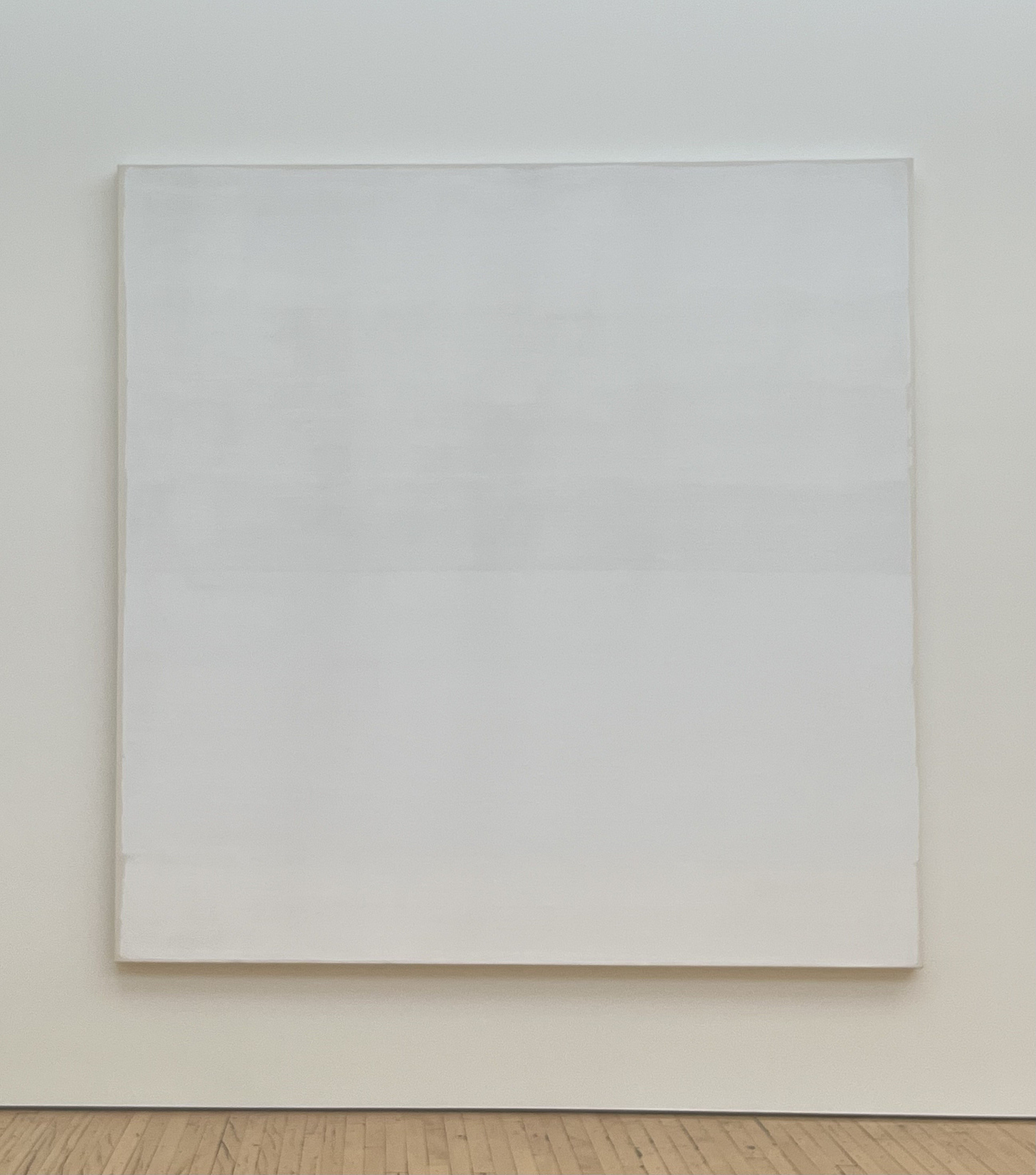

The thing about whiteness is that it’s hard to paint precisely because it’s everywhere and in everything, and I mean this in terms of any kind of whiteness. It’s the image of the world. And yet no one can see it for itself because there’s no such thing as an ipseity of white…Even right out of the tube, there’s titanium white, zinc white, foundation white, flake white. There’s one drop of yellow, one drop of black, three drops of red, two drops of blue and then you have ecru, ivory, alabaster, cream, eggshell. There was first lead white, which we used for millennia, but it was poison.

Johanna Hedva, Your Love Is Not Good

I am working on a writing project, a play with one man and one woman, where my first instinct was to cast one of my white friends. Though the character has been swimming around my head for over a year and I am undertaking the arduous task of wrangling prose from the 1990s and my own interventions from 2025 into a viable theatrical form—adaptation is at first easy and then very hard—I did not cast myself. I have been desperate for some director to choose me, but when I held all the cards I could not see past my rolodex of white women. Those I find beautiful and inspiring. Whose voices I could hear in the rhythms of the dialogue, whose red and blonde hair I could see haloing diaphanous under stage light. Of course this was alarming, all the more so because it was sub-, or rather pre-conscious. My friend Auguste pointed it out to me: why would you not do it? Me? What would that mean for the story? Would it reach the same kind of universality? Would it then be a “black story,” it doesn’t really fit as such…is anything a black story if I myself am black? The angst was actually over rather quickly, not my first rodeo etc., but in its wake, two churning categories of thought: the white muse and the black artist. As per usual, the books I needed dropped right into my lap. Your Love Is Not Good by Johanna Hedva and Minor Black Figures by Brandon Taylor. Both follow a poc artist (white-passing Korean and black, respectively) who is creatively blocked until they encounter their subject, who either happens to be or maybe necessarily is white.

Hedva’s unnamed narrator is at an impasse. She lives in her studio, racking up debts to her gallerist. She semi-haunts the shows of her more “radical” contemporaries (the shows of these more visibly marginalized artists are depicted as self-cannibalizing, making art about the racism/sexism/classism of making art, calling out the museum directors within the commissioned piece, etc). She texts her best friend. She stares at the wall. Into this sucking void of inspiration walks Hanne (“The Twin”), whom the narrator first spies at a party and who coincidentally responds to an ad she places for models. After their first photo session, the narrator is struck by the commercial power of her subject, how the whiteness—distinct from the narrator’s own craft, the subject’s own beauty—will sell.

There was her long, straight, blond hair and pale eyes with lids that creased, her apple-shaped face with tawny skin…She really was beautiful in the empty, vast way that everyone would agree on. I thought about her status as my first white muse…it would carry this new series, carry me, the succeeding that whiteness does to beauty.

Hedva does a remarkable job of highlighting whiteness as a force, usually omnipresent like a dense fog everyone has grown accustomed to, but also graftable, something not all that interesting in itself that can supercharge what it is added to. I have spent a lot of my life considering my relationship to whiteness and beauty. It has been a long time since I considered that one equaled the other, but until I’d read the above I wasn’t settled in my understanding of their connection, because they certainly are linked. Once I dispelled the belief that whiteness was inherently beautiful, I had to wonder why it was so often presented as such.1 Hedva leaves beauty alone to be as capacious or narrow as the reader imagines, and pushes whiteness onto it, and the result of that is success, a new thing that neither beauty nor whiteness necessarily had at the beginning of their courtship.

Looking at the Twin’s face now, I knew it would sell, not just as a commodity but as a concept…the consensus would be universal. I’d never been universal before. Someone like me isn’t.

What I felt, I think, in the moment that Auguste pointed me out to myself, was a preoccupation with whiteness, rather than a jealousy. This is the draw of the muse, but also all tangled up in the crosshairs of race-based desire and rejection. There is something to knowing your work will be appealing to others with a white subject. But, I think, what I was leaning on, what the artist in Hedva’s book captures, is a default laziness that in some ways must be at work to make something “universal” as it is being used in this case—not something sublime and portending to all, but something the most easily digested by the most people. Like broth, or mash, or applesauce.

To me, the universality of whiteness is about habit. Returning to the image of fog, it kind of sits on your shoulders, weighing you down into what might feel like a comfortable slouch but is actually slowly crushing you into non-existence. To be less poetic: I do not think when I see two white people onstage. I do not wonder where they are from or why they are together now. I am not required to. I am completely lulled into the circumstances of whatever story they are acting out. And so, for the non-white artist, for myself, I think the turn to a white subject is actually a desire to be left alone. For the art to say whatever the art is saying without stupid questions.

In the opening pages of Minor Black Figures, Wyeth, another stalled painter, is trying to move himself away from painting what he likes—scenes from 20th century European films transposed with black people—in an effort to work through both external critiques and an internal block about his work. Though to himself, Wyeth is responding honestly to what he’s drawn to in the films—panels of light, coy expressions, moments of incongruous tenderness—the fact that he interjects black subjects is seen as just that, a disruption, and one that must be explained beyond the boundaries of the work itself: “…the two black women in such a setting had to have some accounting for how they had come to be there. This tension, this disbelief needing suspension, led people to say strange things about Wyeth’s paintings.”

Throughout the book it is clear that Wyeth really aches to be taken on his own terms, both in art and in his personal life, even when he is not so clear on what those terms are. As is typical of Taylor’s style (in essay and in fiction), he is able to distill this conflict in the kind of casually salient conversations one can end up having with friends, all the appearance of just tossing something back and forth, but the thing is like… a priceless glass egg with real yolk inside. It’s difficult for me not to reproduce this whole section (pgs. 254-263 for those following along at home), but for brief context: Wyeth and his co-worker/friend Chloé are discussing a black artist whose work they are restoring which leads to a conversation on the exploding market for “black art” following the murder of George Floyd and Wyeth’s accidental small profit off of that explosion and then to where he stands in the middle of art and its market and his race.

“How to paint black life without feeling like you’re in it for the wrong reasons,” she said.

“Not even that,” Wyeth said. “How to paint life as a black person, with black people, not black figures, people, and not have…all the stuff attached.”

“That’s interesting,” Chloe said.

“What?”

“That you want to paint people but not have all the stuff attached,” she said. “For some, all the stuff is the whole point.”

“I mean all the…you know, free standing race stuff.”

“Sure, but that is an aspect of black life,” she said. “You don’t get to exempt yourself or your figures from it because you find it inconvenient.”

“But white people don’t have to deal with it,” he said.

“They do,” she said. “They call it something else. Class, maybe.” She smiled wryly at him. “Or gender. Sexuality. They have a lot of names for it. But it’s the same thing. All the stuff, as you call it, is…life, Wyeth. It’s living in the world. It’s systems. Even white people have to contend with systems. All their shit is genre painting too.”

“Sure,” Wyeth said, feeling a little chastened. “Okay, yeah, I agree but…”

“The issue,” she said, “is that you want to be taken on your own terms, is that right? As an individual?”

“Yeah,” he said.

“Right, so that’s never going to happen. Which is not your fault. That’s just, you know, the nature of Caucasian eyeballs.”

“Depressing,” he said.

In the play I am working on2the juiciest questions are about sex, fantasy, intimacy, vulnerability between strangers, concentric circles of truth, all things I would like people to attend to and wondered if I would get in the way of. I return to Taylor’s phrase, disbelief needing suspension—will people see all of those things if a black woman and a white man are onstage, a black woman and a black man? It is silly on the one hand but also completely serious on the other because this is something I (we) are forced to think about. Who is this for? How will they receive it? Do I even care? When, if I do care, should I care? I was recently in a reading of a play with all black folks that was itself about being black in america. It was a beautiful room of collaborators and we all felt, to varying degrees, the sanctity of that closed room, the dangers and disappointments of not even misperception but perception that waited on the other side of the door. There was a scene, stunning when read, that the group then wondered if a general (white) audience should even see.

I have no conclusion, I am merely pondering. It actually took me so long to write this because I thought I had a conclusion but it was actually just a feeling. Nina sent me this very amusing list of writing rules and when I read number 7 I knew I was in trouble. In part: “All emotions are useful for writing except for bitterness.” It is “three inches of brackish water. Nothing lives in it. You can stand in it and see the bottom.” I don’t know if I was feeling bitter per se, but my stunted drafts were oscillating between a kind of petulance and apology that made very little space for curiosity. Also I’m reading again, so you know the thoughts are flowing. And I’m taking Garth Greenwell’s class on Confessions so you knooowwwwww I am thinking about thinking more than ever. My notes from class 1 include: to remember, to retrospect is to call something back into the heart / this is salvific because it gathers again what has been scattered / self-narration is to participate in salvation, one is recollecting oneself. So you already know I’ll have to write an entire (completely circular and rambling like this one) essay about that.

xx

Mia

This is something I have trouble explaining when I recount coming into race-consciousness: the need for replacement and the dissonance between what you are told and what you see enacted in the world. It might be why I have found myself in deeply empathetic friendships with people who have left a consuming religious order.

“Working” is generous to the point of being a lie. I have been at an absolute standstill for want of time. And basically this whole thing is irrelevant if I don’t actually finish my next draft so I am planning to take myself away on a one-week retreat in January if anyone wants to join.

![[TITLE CARD HERE]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!SUJW!,w_40,h_40,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fd0a7fd49-8c28-4108-8d36-8d3fa76673ad_1080x1080.png)

Heavy!

Whiteness is something I am exhausted by but there's power in naming it so that it doesn't continue to be this omnipresent invisible asphyxiation. What a tricky, but necessary, slope to navigate. Thank you for sharing <3